By Jason Burton, MD

VCU Health System

Richmond, VA

Recently, while teaching medical students the Clock Drawing Test (CDT), I realized I was surrounded by a group wearing smartwatches. This made me reflect on something I’ve thought about before, but that felt particularly relevant that day: Is the CDT becoming outdated? Even the phrasing we use when describing the time—”make it 10 past 11”—seems antiquated and might not be understood by future generations. While there’s no impending crisis of inability to assess cognitive dysfunction if the CDT becomes extinct, I can’t help but feel a bit nostalgic when considering the future of the CDT. I think the CDT’s days may be numbered.

That said, for now, the CDT remains a simple yet invaluable tool for assessing cognitive function, and it’s certainly worth revisiting and reviewing as we continue using it in clinical practice.

The CDT is widely used in psychiatry to evaluate executive functions, spatial awareness, and overall cognitive abilities. Developed in the 20th century and popularized in the 1980s, it serves as a quick, effective method for screening patients for signs of cognitive impairment, especially among older adults at risk for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.1 For psychiatrists, the CDT provides a unique window into the cognitive functions that more traditional methods, such as questionnaires, may not fully reveal. The CDT is versatile, easy to administer, adaptable to various clinical settings, and cheap. It is best used as part of a larger neuropsychological evaluation, complemented by tests like the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).

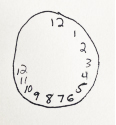

The CDT is straightforward: patients are given a blank sheet and asked to draw a clock showing a specified time, usually “10 past 11.” They must draw a circle, place numbers accurately within the circle, and position the hands correctly. This seemingly simple task assesses several cognitive domains, including visuospatial skills, planning, and numerical sequencing.

Interpreting the CDT requires nuance, as it is not particularly sensitive or specific for pinpointing dysfunction in one particular brain area.2 Instead, it offers a general glimpse into cognitive function, adding information to be considered within the larger clinical picture. Still, certain common errors can hint at specific cognitive dysfunctions or suggest the involvement of certain brain regions. Here are some common CDT mistakes and the types of disorders in which they appear.

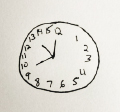

Pull-to-Stimulus Error

When giving the instruction—”draw a clock and set it to 10 past 11”—the numbers “10” and “11” serve as stimuli. A person with frontal lobe dysfunction may place the clock hands on the 10 and 11, rather than correctly setting the long hand on the 2. This error, known as “pull-to-the-stimulus,” reflects the frontal lobe’s role in inhibiting this automatic response and correctly interpreting the task.

Perseveration

Drawing multiple hands, multiple circles, or continuing to place numbers past 12 may indicate perseveration from a poorly functioning frontal lobe.

Spatial and Planning Deficits

Spatial and planning deficits appear as layout errors in the clock drawing. Common examples include neglecting the left side of the clock, uneven spacing between numbers, disorganized arrangement, and numbers placed outside the clock face. These deficits are more frequently observed in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) compared to other dementias or might be due to a stroke.3 Such errors often arise from impairments in the non-dominant right hemisphere, especially the right parietal lobe.

Graphical Difficulties

Graphical difficulties occur when lines lack precision, causing distortions in the clock face or making numbers challenging to read. The clock hands may appear uneven or jagged or not meet at the center. Although the drawing typically remains identifiable as a clock, it seems inaccurate overall. These graphical errors are more frequently seen in conditions like Huntington’s disease and vascular dementia.4

References

- Hazan E, Frankenburg F, Brenkel M, Shulman K. The test of time: a history of clock drawing. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018 Jan;33(1):e22-e30. doi: 10.1002/gps.4731. Epub 2017 May 26. PMID: 28556262.

- Heyrani R, Sarabi-Jamab A, Grafman J, Asadi N, Soltani S, Mirfazeli FS, Almasi-Dooghaei M, Shariat SV, Jahanbakhshi A, Khoeini T, Joghataei MT. Limits on using the clock drawing test as a measure to evaluate patients with neurological disorders. BMC Neurol. 2022 Dec 31;22(1):509. doi: 10.1186/s12883-022-03035-z. PMID: 36585622; PMCID: PMC9805016.

- Blair M, Kertesz A, McMonagle P, et al: Quantitative andqualitative analyses of clock-drawing in frontotemporal de-mentia and Alzheimer’s disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2006;12:159–165

- Kitabayashi Y, Ueda H, Narumoto J, et al: Qualitative analysesof clock-drawings in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular de-mentia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001; 55:485–491